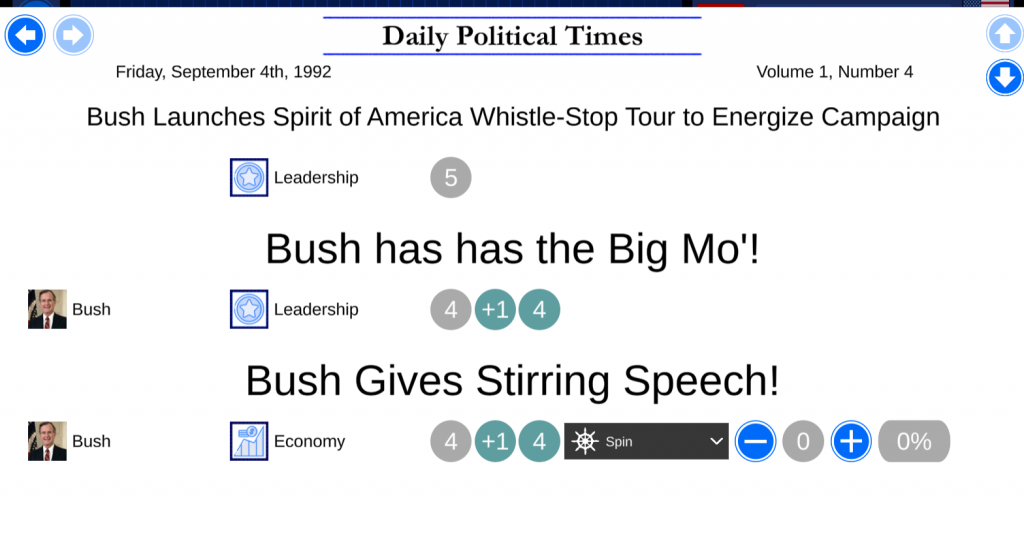

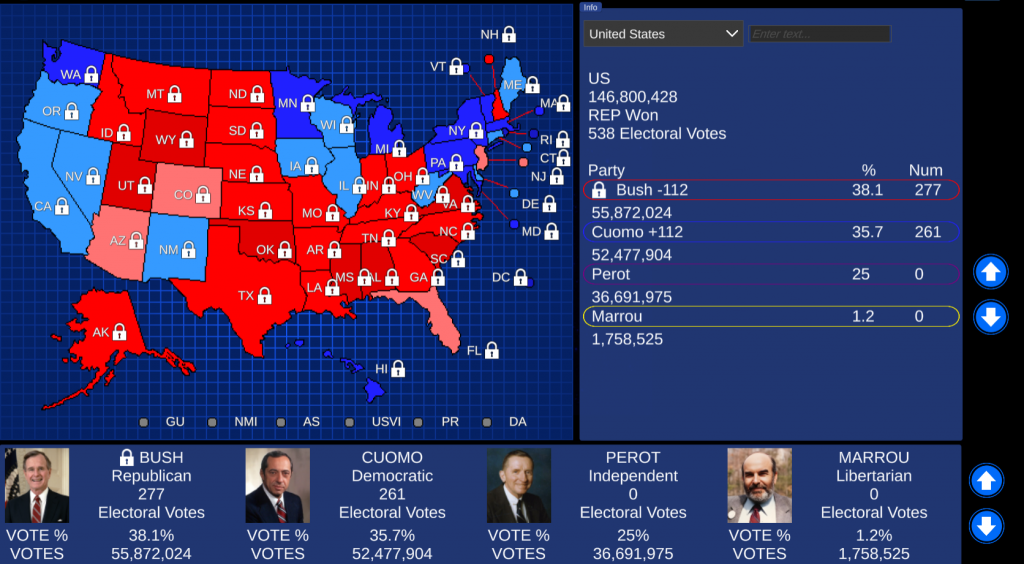

The 1992 U.S. presidential election begins as what many assumed would be a straightforward re-election campaign for President George H. W. Bush, whose popularity had soared to historic highs—reaching nearly 90% approval—after the successful conclusion of Operation Desert Storm and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Bush had presided over a foreign policy triumph that reasserted American power on the world stage and ushered in what many saw as a unipolar moment of U.S. dominance. Few doubted his chances for a second term.

But the domestic situation told a very different story.

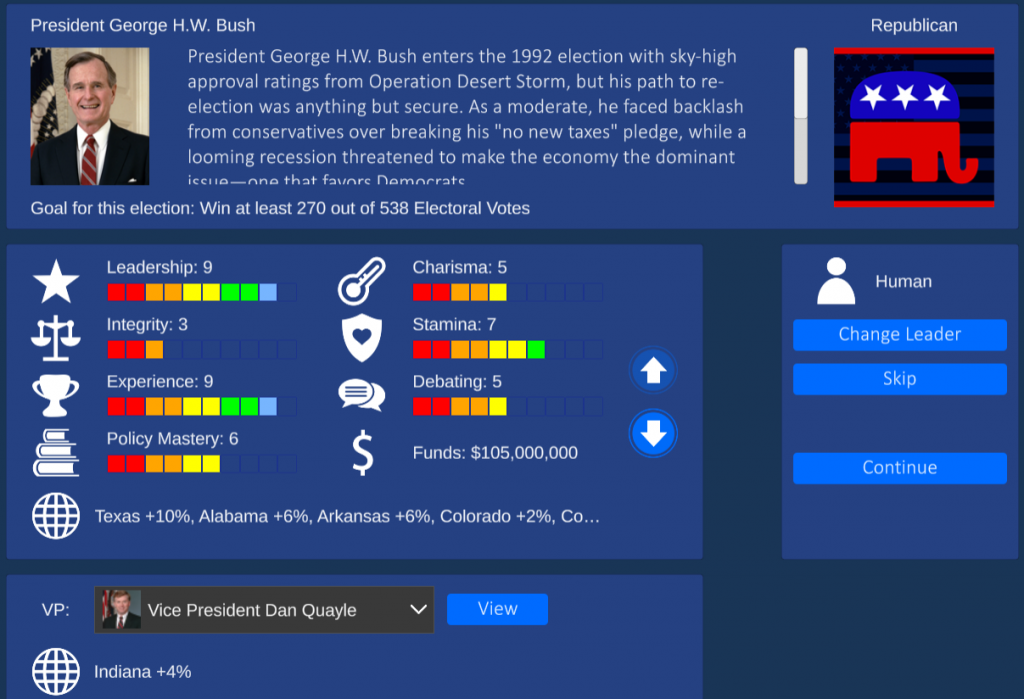

By late 1991 and into 1992, the U.S. economy had slipped into recession, with rising unemployment and stagnant growth. Voters’ attention shifted from foreign affairs to pocketbook issues, and the glow of Bush’s Gulf War success began to fade. Adding to his vulnerability was his 1990 decision to break his famous “Read my lips: no new taxes” pledge—an act seen by conservatives as a betrayal and by moderates as ineffective. Bush now faced the difficult choice of how to define his political identity: would he double down as the pragmatic moderate who raised taxes to deal with the deficit, or pivot sharply to the right and stoke the culture wars in a bid to shore up the GOP base?

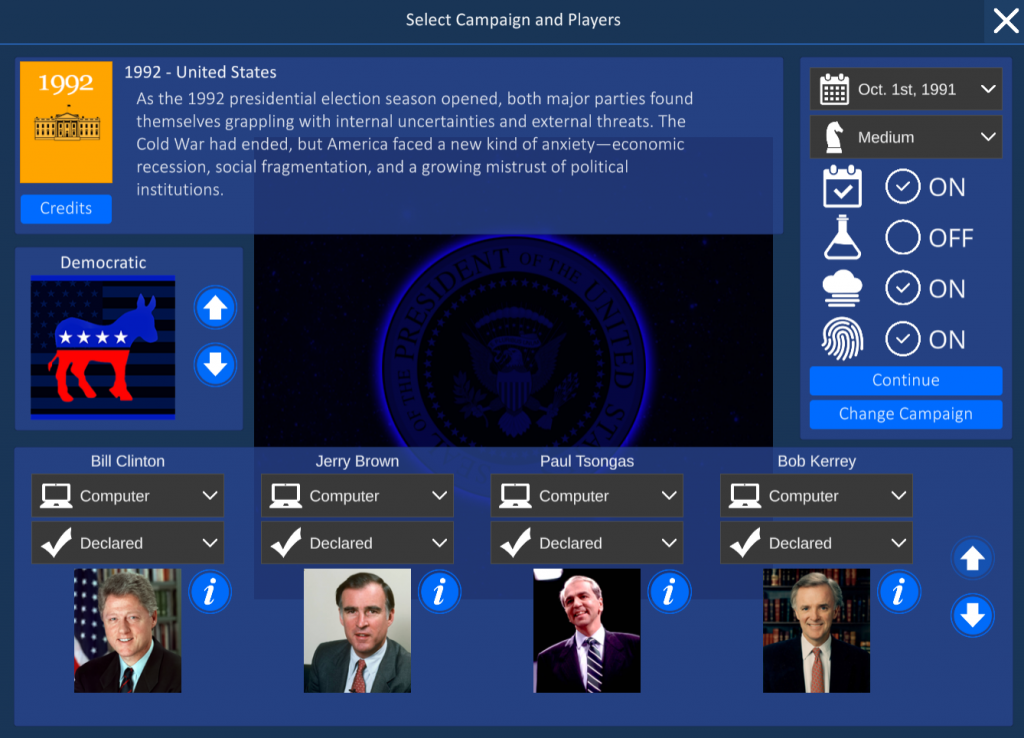

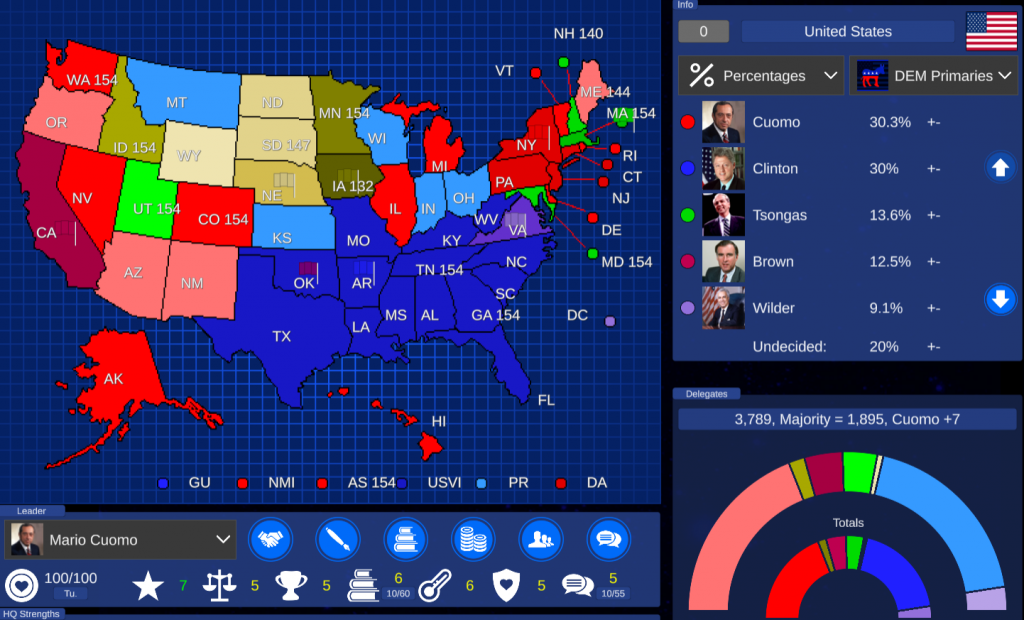

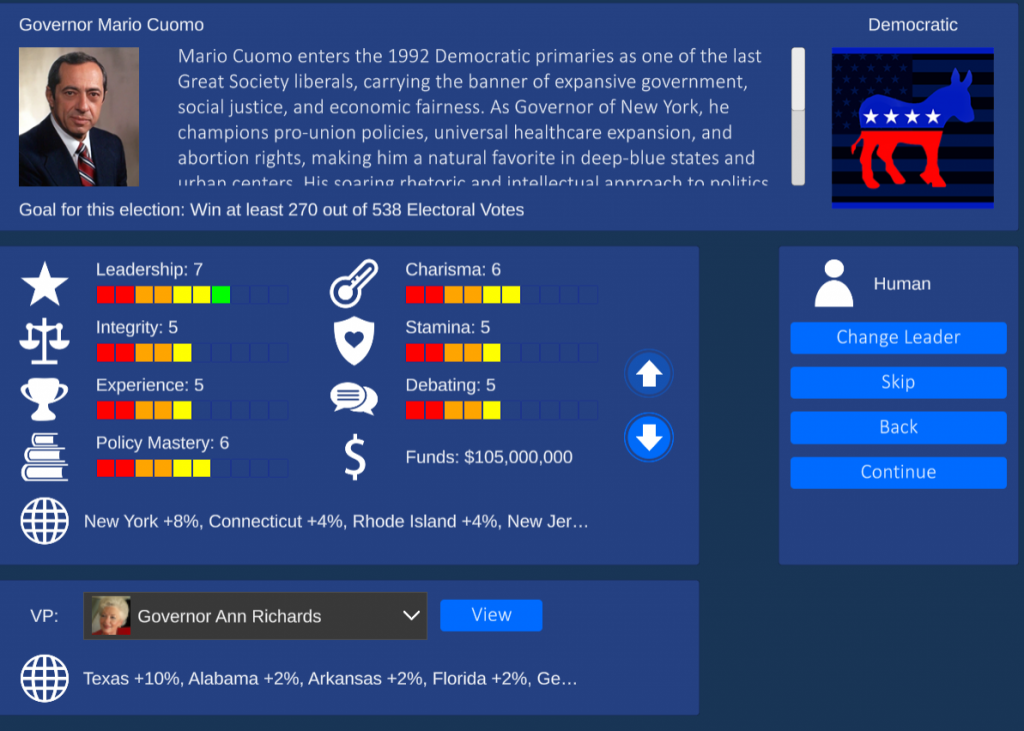

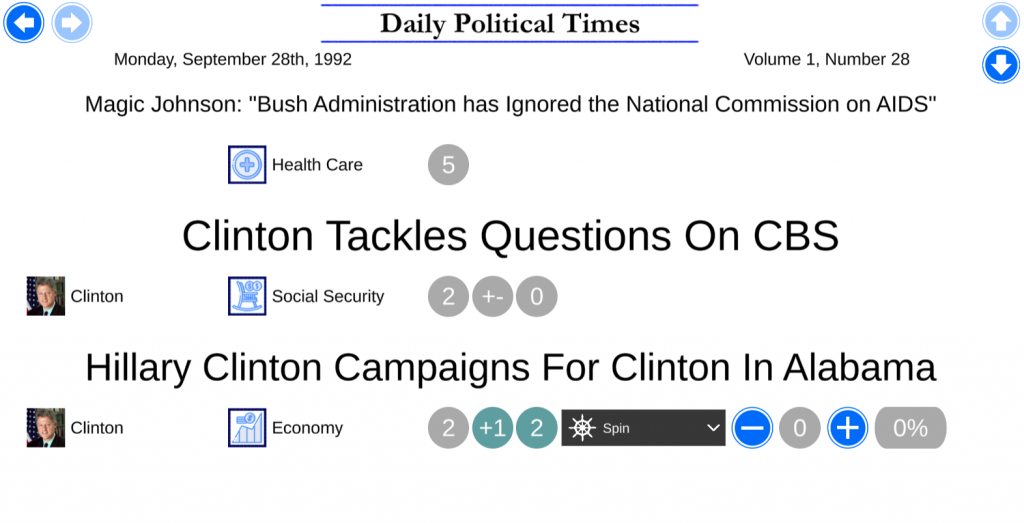

For Democrats, the shift in economic mood opened an unexpected door. Initially, many big-name Democrats declined to run, convinced that Bush’s towering approval ratings made 1992 unwinnable. Into that vacuum stepped a relatively unknown governor from Arkansas, Bill Clinton, who would soon surprise the political world by emerging as a charismatic, energetic campaigner with a focus on the economy—“It’s the economy, stupid”—and an ability to triangulate between traditional liberalism and emerging centrist themes.

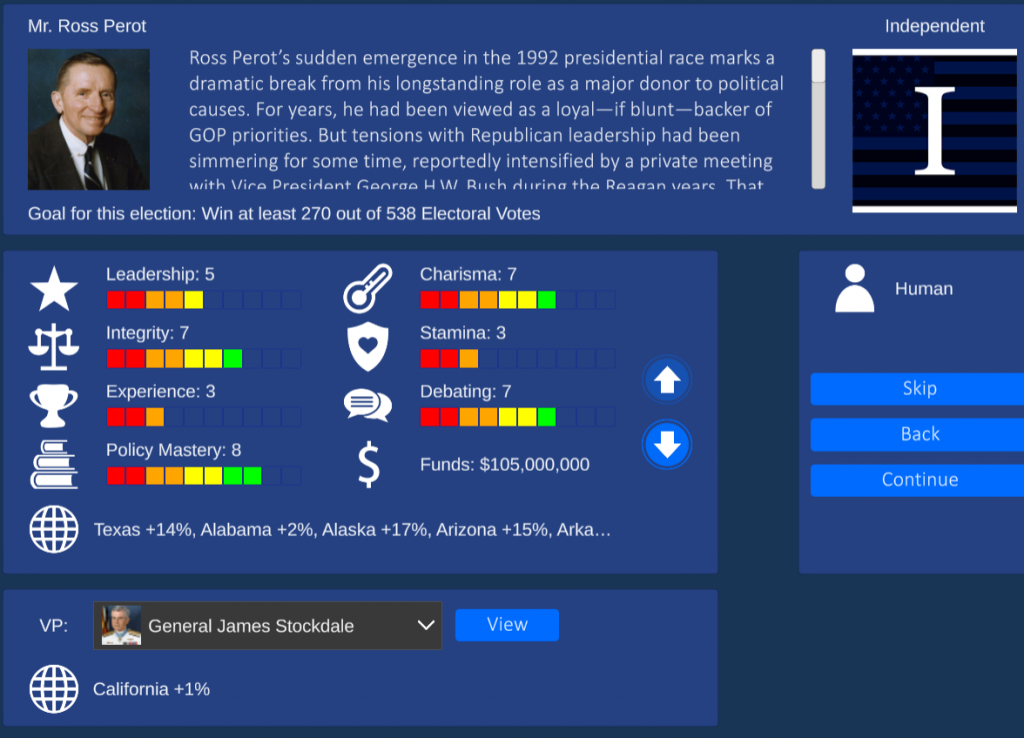

Meanwhile, the wild card of the race is Ross Perot, a Texas billionaire and self-financed independent candidate who tapped into a rising wave of public frustration with both parties. Perot’s message about the national debt, trade imbalances, and political dysfunction resonated with a broad spectrum of voters. At one point in the spring of 1992, Perot led both Bush and Clinton in national polls. Though he temporarily dropped out in July—only to re-enter the race later in the fall—his insurgent candidacy showed how volatile the electorate had become.

Now, heading into the general election, the 1992 race is anything but predictable. Bush is wounded but still formidable, Clinton is rising with momentum and a modern campaign apparatus, and Perot lurks on the sidelines, capable of jumping back in and upending the race again. With a faltering economy, ideological divisions within the Republican Party, and a Democratic Party trying to redefine itself for a post-Cold War America, the election is wide open. Anything can happen.

Download: https://www.mediafire.com/file/mellv92exyrp0no/United+States+-+1992.zip/file